I wanted to share a few things about some of the songs that you’ve heard during services over the past few weeks. When the ministry team plans and shapes Sunday services – guided by the marvelous Rev. María Cristina – we work to make sure everything fits as a whole. Finding music that fits the theme and is singable and/or memorable is a fun challenge. I love doing research, and I love finding new songs to love and share.

Gracias a la Vida: September 18

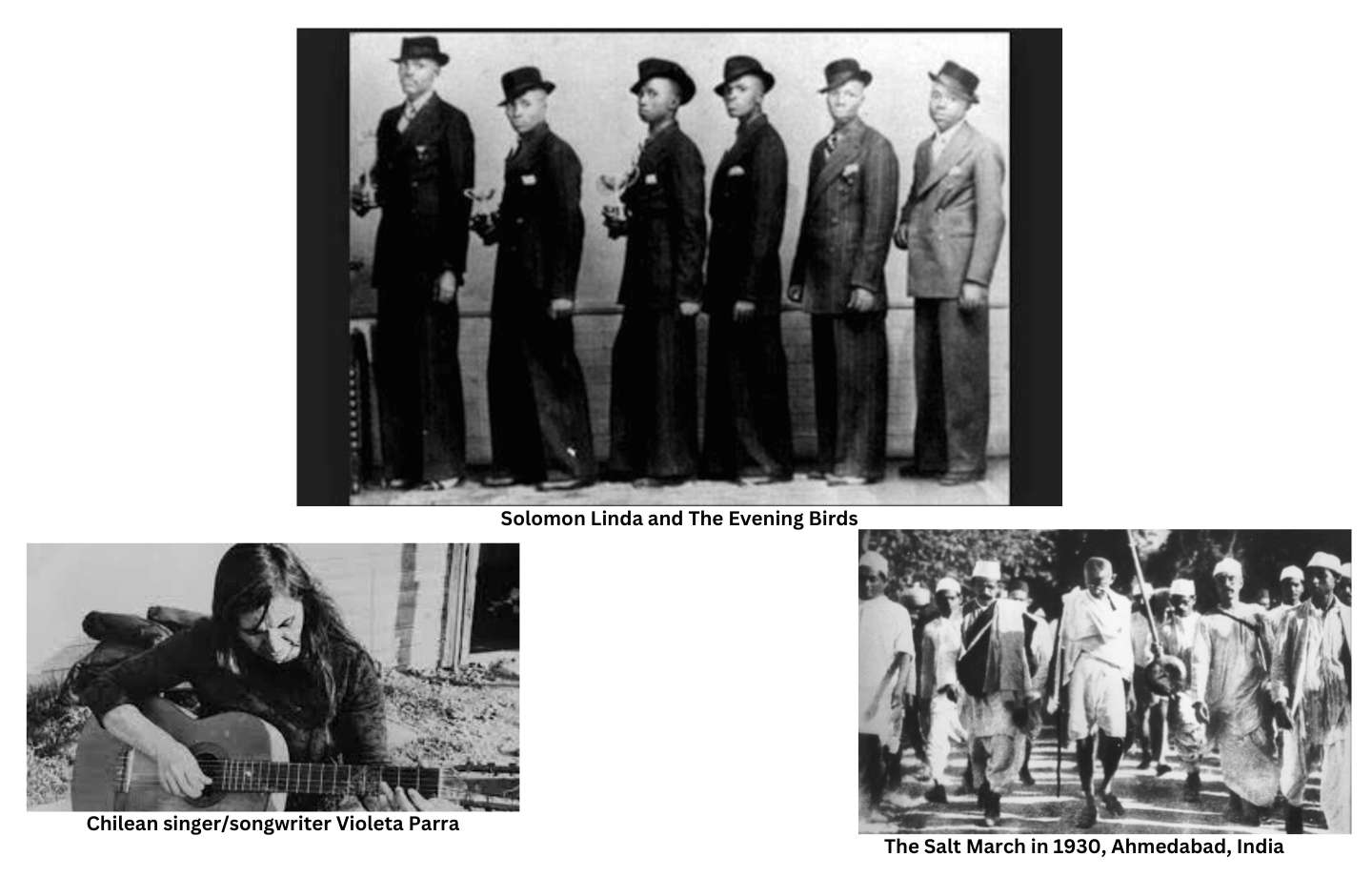

One of these songs is ‘Gracias a la Vida,’ which Mama Lily sang on September 18 for Rev. María Cristina’s birthday. This is a song that has a rich cultural history. It was written by Chilean singer/songwriter Violeta Parra. She was part of the movement and musical genre known as the ‘Nueva Cancíon Chilena,’ or ‘New Chilean Song.’ This movement was strongly political and social; the songs reflected a deep spirit of community and history as they were sung in protest to the political upheavals happening in the region. ‘Gracias a la Vida’ has been called a ‘humanist hymn,’ as it basically gives thanks to Life Itself for the innumerable wonders of the earth and the human family. When Mama Lily sang the song, she sang ‘Gracias mi hija,’ (Thank you, my daughter.) The song has meant a lot to both Rev. María Cristina and her mother throughout their lives.

The Lion Sleeps Tonight

In looking for songs for the Blessing of the Animals service, I wanted something up-beat and fun for the postlude. The Lion Sleeps Tonight (or Wimoweh) came to mind. It was easy for the choir to learn, and we had a lot of fun closing the service out with it. But I made myself a promise that I would share the background of the song with all of you. It is a troubled history, and reflects a lot of what often happens when someone co-opts a piece of another culture’s heritage.

South African singer and songwriter Solomon Linda wrote and recorded Mbube in the ‘30s with his group The Evening Birds. The song was based on a traditional pattern of Zulu singing, with a call and response pattern. The word “Mbube” means “lion” in Zulu, and the original song was intended as a plea for lions to leave sheep alone during the night. The Evening Birds’ recording became a hit in South Africa throughout the 1940s. The song’s title gave the name to the style of African a cappella music called mbube, with Ladysmith Black Mambazo bringing the style to worldwide focus in the 1980s.

In 1949 music ethnologist and historian Alan Lomax brought a copy of Mbube to his friend Pete Seeger. Seeger and his group The Weavers, made a recording of an adaptation of the song in 1951 called Wimoweh. (This was a mishearing of the word “Uyimbube” which means “you are a lion” in Zulu, which was repeated in the chorus of the original.) The Weavers credited the song as “Traditional.” It reached the Billboard top ten, and several others began to record the song as well, including The Kingston Trio and Yma Sumac. None of these singers gave Solomon Linda credit for having written the original. It has been reported that The Weavers thought they were singing and recording a traditional African folksong. It is true that the song we know of as The Lion Sleeps Tonight is rather different from the original Mbube, eventually including the words most of us associate with the song: “In the jungle, the mighty jungle, the lion sleeps tonight.” At the same time it is clear the Zulu song was the inspiration for the Americanized version. In 1961, The Tokens recorded The Lion Sleeps Tonight. The song rocketed to the #1 slot on the Billboard Hot 100. Pete Seeger was contacted by Solomon Linda’s record company and Seeger sent $1,000 to Linda, and instructed his and the Weavers’ publishing company to pay a fair share of the royalties to Linda henceforth. This didn’t happen and Solomon Linda died destitute in 1962 as white American publishing and recording companies were reaping millions from the song.

In 2000, South African journalist Rian Malan wrote a feature article for Rolling Stone magazine in which he recounted Linda’s story and estimated that the song had earned $15 million for its use in the Disney movie The Lion King alone. This piece prompted filmmaker François Verster to create the Emmy-winning documentary A Lion’s Trail, that told Linda’s story while incidentally exposing the workings of the multi-million dollar music industry.

In July 2004, as a result of the publicity generated by Malan’s article and the subsequent documentary, the song became the subject of a lawsuit between Linda’s estate and Disney, claiming that Disney owed $1.6 million in royalties for the use of The Lion Sleeps Tonight in the film and musical stage productions of The Lion King. In February 2006, Linda’s descendants reached a legal settlement with Abilene Music Publishers, who held the worldwide rights and had licensed the song to Disney, to place the earnings of the song in the Solomon Linda Trust, 45% of which will go to Linda’s descendants.

In 2012, Mbube fell into the public domain, owing to the copyright laws of South Africa. The Lion Sleeps Tonight, however, still remains in copyright.

This tale is sad and infuriating enough on its own. But it is one that has been repeated time and time again in the history of popular music in the USA. Music written and originally performed by People of Color has been routinely repackaged by white singers who made small fortunes off of the material. The original artists were rarely compensated, or led to signing ridiculously unfair contracts to gain copyright ownership of their original songs. Being a writer/composer/publisher myself (as well as a person of conscience) I always want to make sure credit is given where credit is due. As much as possible, I strive to lift up historically under-represented voices in music. And, whenever possible, I strive to make sure appropriate compensation is given.

Raghupati: October 23

There is one more bit of musical background I’d like to give. This is for a song from our Diwali service. The song ‘Raghupati’ is in the gray hymnbook, and is credited as a ‘traditional Hindu hymn.’ This much is true, as the precise origins of the song are not entirely clear. It was either written by the Hindu saint and poet Tulsidas during his life in the 17th century or by the Marathi saint-poet Ramdas (not to be confused with the 20th century writer and spiritual teacher Ram Dass.) The tune was set by Vishnu Digambar Paluskar to the raga gara in the early 1900s. The song known as ‘Raghuputi’ has undergone several transformations as a Hindu devotional hymn, but the most well-known version is that adapted by Mahatma Gandhi. His version is an ecumenical one, stating that the Ishvara (Supreme Being) of Hindu and the Allah of Islam were one. ‘Raghaputi’ was used by Gandhi and his many followers to spread the message of reconciliation between Hindus and Muslims. It was also sung during the 1930 Salt March, an act of nonviolent civil disobedience in colonial India led by Gandhi. The words appear in our hymnal as a transliteration of the Hindi version of the prayer. The translation says:

O Lord Rama, descendant of Raghu, Uplifter of the fallen

You and your beloved consort Sita are to be worshiped.

All names of God refer to the same Supreme Being

Including Ishvara and the Muslim Allah.

O Lord, please give peace and fellowship to everyone, as we are your children.

We all request that this eternal wisdom of humankind prevails.

My friend Swapnesh Dubey, who did the service this year, also provided a talk on Diwali two years ago via video, one that urged more equity between men and women in India. As a result of this take Swapnesh received several threats from nationalistic Hindus who saw his presentation as being anti-Hindu and (to them) anti-India. (This is why the video was removed from East Shore’s YouTube site.) When I spoke with Swapnesh about music for this year’s Diwali service he enthusiastically agreed that ‘Raghuputi’ would be a fitting song, as it mentions Sita and Rama, the two central figures in the story of Diwali. I researched several versions of the song (including one by Pete Seeger!) and found quite a large variety of styles and takes. One on site I found a recording that was put forth as the ‘original and authentic’ version of the song, decrying Gandhi’s ‘bastardized’ version as being against Hinduism. It seems nationalism and fundamentalism often go hand in hand and can happen in any country or nationality that claims a certain religion to be the One Whole Truth. We’ve certainly seen a lot of that here in the United States, with many people claiming our country is a ‘Christian nation’ and that it was the founding fathers’ intention to stake that claim. I prefer the gentle, compassionate way of radical inclusion. Lines that are drawn to demarcate ‘us’ and ‘them’ seem always to be drawn with fear or anger, and often with violence as a result. I hope everyone enjoys our version of ‘Raghuputi,’ the version championed by Mahatma Gandhi, one of the great souls of the modern age.

Website Page

On a final note: Nicole and I are working on a website feature that will allow me to share more such background stories of music presented at East Shore, as well as informational tidbits and an occasional musical anecdote. More as this story (and website feature) develops!

by Eric Lane Barnes, Director of Music